Frederick Brown, The Battle for the Soul of France; Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus

Origins of the Conflict

AFTER OBSERVING THE pilgrims thronging Lourdes in 1891, Emile  Zola noted that the time and setting were right for a novel about the intractability of mankind's dependence upon the miraculous. "Study and dramatize the endless duel between science and the longing for supernatural intervention," he instructed himself. The theme pervades his great fictional cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart, in which modernity is dogged by the pious and the primitive. Rural folk who aspire to a higher level of awareness are weighed down by the archaic baggage they carry with them; bourgeois women surrender to a priest's erotica-mystical predation. Everywhere, the Church casts a long shadow.

Zola noted that the time and setting were right for a novel about the intractability of mankind's dependence upon the miraculous. "Study and dramatize the endless duel between science and the longing for supernatural intervention," he instructed himself. The theme pervades his great fictional cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart, in which modernity is dogged by the pious and the primitive. Rural folk who aspire to a higher level of awareness are weighed down by the archaic baggage they carry with them; bourgeois women surrender to a priest's erotica-mystical predation. Everywhere, the Church casts a long shadow.

"Science" and "supernatural intervention" were indeed the competing prescriptions for France's recovery after the Franco-Prussian debacle of 1870-7 1, which toppled Napoleon III from his Imperial throne. These alternatives informed her social, political, and cultural life in the last third of the century, framing a bitter debate over the country's heart and soul. It's as if a nation divided needed only humiliation at the hands of a foreigner to turn upon itself and wage without restraint the civil war that had long excited its most implacable hatred.

For everyone, 1789 was the inevitable reference point.

There were those on the one hand who held that France would betray the best of herself if she did not remain loyal to the eighteenth century thinkers who had fathered the Republic. On the other hand, "intransigeants" committed to the ideal of a Catholic monarchy anathematized the Enlightenment. In their view, divine grace was needed, and France could receive it only as a penitent mindful of the sins she had accumulated over the course of eighty years.

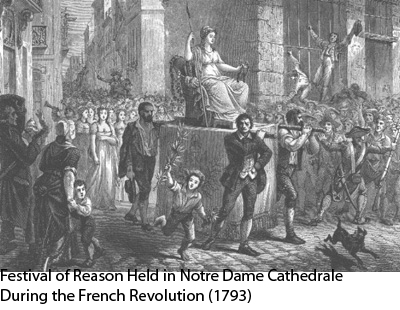

How THIS IMPASSE was reached is worth examining. The battle line was first boldly drawn during the Revolution -- when clergy who would not pledge allegiance to the republican constitution risked exile or death, when saints' days were expunged from the calendar and Church property amounting to a fifth of France was seized by the State to be auctioned off. Men contemptuous of the Scriptures staged a service honoring Reason at Notre-Dame cathedral. By 1801 Napoleon

first boldly drawn during the Revolution -- when clergy who would not pledge allegiance to the republican constitution risked exile or death, when saints' days were expunged from the calendar and Church property amounting to a fifth of France was seized by the State to be auctioned off. Men contemptuous of the Scriptures staged a service honoring Reason at Notre-Dame cathedral. By 1801 Napoleon

Bonaparte had gained power as First Consul. Mistrustful of anything clandestine, he negotiated with Pope Pius VII a treaty, or Concordat, that granted permission to worship "openly" and "freely" while reserving for himself the right to map dioceses and appoint prelates: Gallican bishops. The Church was visible, but only as an emaciated shadow of itself, with far fewer parishes than before1789, and no priests to serve many of them. Young men who at one time might have taken vows were instead fighting and dying all over Europe. Clerical black enjoyed little prestige in a military state that treated the curate as a minor agent of social order.

The downfall of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 was thus an occasion for  celebratory masses. Repatriated nobles and clerics went about setting things right. In 1797, Louis XVI's brother, the exiled Comte de Provence, had instructed exiled French bishops never to forswear the marriage of throne and altar. "How indispensable it is that they support each other! May ecclesiastics imbue my subjects with this truth. . . . The marvelous order that is the Catholic Church will not long survive uniess it remain bound to the Monarchy." Eighteen years later, as King Louis XVIII, he restored the Church to its eminence, replacing Napoleonic functionaries with an episcopate of high ranking aristocrats. Catholicism became once again the state religion. Religious orders reestablished themselves. Writing disrespectfully about the Church or insulting a priest constituted grounds for imprisonment; destroying liturgical objects was punishable as a capital crime; dolor and ecclesiastical pomp informed civil life; and a secret society called Knights of the Faith ("Chevaliers de la Foi") controlled patronage. To those émigrés in whom loss had fostered humility, what often mattered most was the consolation they found in religion for their immense reversals of fortune. Not unlike the thousands who flocked to pilgrimage sites after the Franco-Prussian War half a century later, they prayed with fervor. . . .

celebratory masses. Repatriated nobles and clerics went about setting things right. In 1797, Louis XVI's brother, the exiled Comte de Provence, had instructed exiled French bishops never to forswear the marriage of throne and altar. "How indispensable it is that they support each other! May ecclesiastics imbue my subjects with this truth. . . . The marvelous order that is the Catholic Church will not long survive uniess it remain bound to the Monarchy." Eighteen years later, as King Louis XVIII, he restored the Church to its eminence, replacing Napoleonic functionaries with an episcopate of high ranking aristocrats. Catholicism became once again the state religion. Religious orders reestablished themselves. Writing disrespectfully about the Church or insulting a priest constituted grounds for imprisonment; destroying liturgical objects was punishable as a capital crime; dolor and ecclesiastical pomp informed civil life; and a secret society called Knights of the Faith ("Chevaliers de la Foi") controlled patronage. To those émigrés in whom loss had fostered humility, what often mattered most was the consolation they found in religion for their immense reversals of fortune. Not unlike the thousands who flocked to pilgrimage sites after the Franco-Prussian War half a century later, they prayed with fervor. . . .